Inside Ukraine’s ‘superhuman’ effort to fit wounded soldiers with bionic limbs

July 10, 2023 | By Vicki Hyman

Vitalii Ivashchuk, a veteran of the Ukrainian military, was living in Poland and returning home from the late shift at dawn on February 24 last year when Russia invaded Ukraine. He immediately tried to buy a bus ticket home to Zhytomyr, about two hours west of Kyiv, but the closest he could get was Lutsk, about 160 miles short of his hometown.

“It was no longer important the city — the main thing was that it is in Ukraine,” he recalls. “I was going to fight for my country.”

Within three days of the invasion, the 24-year-old was part of a combat unit defending first Zhytomyr and then Kyiv. Later in the spring, he was sent to the front lines in the east of Ukraine. He had served in Ukrainian flashpoints before and thought he was an experienced soldier, but he had never seen anything like this — full volleys of shells every two minutes or less. “I realized that until this day,” he says, “I had not fought at all.”

During a tank assault by Russian troops in June 2022, he suffered devastating injuries to his wrist, compounded by cluster bombs that exploded nearby during his evacuation. His arm had to be amputated.

“The next day after the amputation, we were getting dressed in the morning,” he says. “My comrades proposed to help, but I wanted to manage myself. Well, for five minutes, if not more, I put the T-shirt on. I struggled terribly, but I put it on. I don't need help if I don't ask for it myself. If I see that I can't help myself, I will definitely say so.”

Since the invasion, tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers have been wounded in action, according to a leaked assessment by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, and thousands of civilians have been injured. The war has also taken its toll on the health care system, with more than 500 attacks, both targeted and indiscriminate, on hospitals, clinics, ambulances and other health care infrastructure by the end of 2022, according to researchers, and there’s not enough government funding for complex surgeries and expensive prosthetics.

One soldier who lost his right arm and three fingers from his left hand was offered only a heavy wooden arm, recalls Andrey Stavnitser, the owner of a logistics firm headquartered near Odessa. Such heartbreaking stories propelled Stavnitser, his business partner Philipp Grushko, and venture philanthropy expert Olga Rudneva to form the nonprofit Superhumans and an associated modern war trauma center in Lviv. Their work is supported in part by Mastercard, which ran a nationwide fundraising campaign through June 30, doubling consumer donations to the Superhumans Center.

The center, which opened in April, provides free psychological and medical support for soldiers and civilians living with prosthetics. It also offers facial reconstruction and rehabilitation, and it plans to train specialists to serve patients across Ukraine.

Vitalii Ivashchuk, a Ukrainian soldier who lost his left arm in fighting last year, shakes hands with Inga Andreieva, the Mastercard country manager for Ukraine and Moldova. Ivashshuk and another soldier were flown to Munich earlier this year for fitting for his new prosthetic through Superhumans, a Ukrainian nonprofit supported by Mastercard. (Photo courtesy of Mastercard)

Andrii Hidzun lost his arm in a mine explosion in April 2022 but was also fitted with a prosthetic arm through Superhumans, which recently opened a clinic in Lviv for soldiers and civilians injured in the war. (Photo courtesy of Superhumans)

Helder Goncalves is a prosthetist with Open Bionics, which developed the Hero Arm, a lightweight 3D-printed bionic arm. (Photo courtesy of Superhumans)

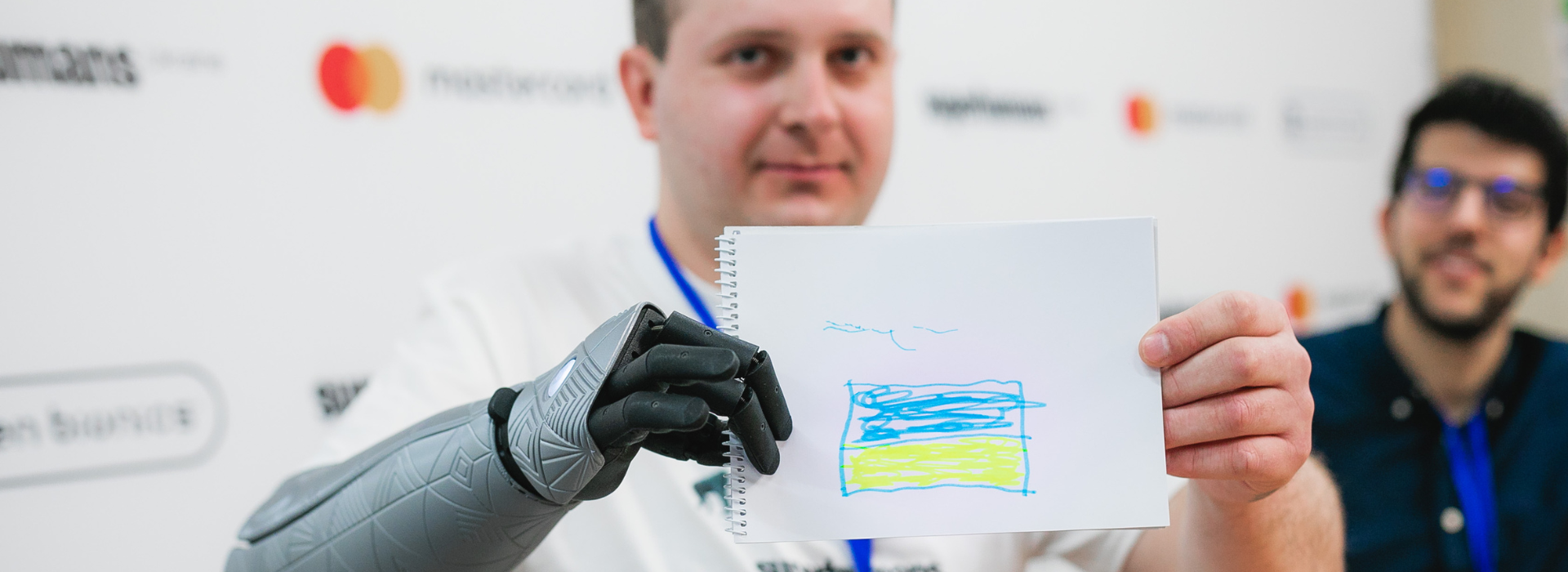

The Hero Arm enables a much wider array of motor skills than other prosthetics, including the ability to grip, grab, pinch and offer high-fives, thumbs-up and fist bumps. (Photo courtesy of Superhumans)

Superhumans CEO Olga Rudneva and Ivashchuk at his fitting in Munich in February. (Photo courtesy of Superhumans)

Denys Kryvenko, left, who lost both legs and an arm while defending the road to Bakhmut, and Petro Buriak, who lost both legs and some fingers in anti-tank mine explosion near Kherson, at the opening of the Superhumans Clinic in Lviv in April. (Photo courtesy of Superhumans)

The Superhumans Clinic in Lviv includes a prosthetics production center, a hydrotherapy pool and a full range of clinical services, including psychologists. It plans to expand its services to six regions of Ukraine by 2025. (Photo courtesy of Superhumans)

“About the name Superhumans — it’s not just the name of the project anymore,” Ukrainian First Lady Olena Zelenska said at the opening of the center in April. “This, in my opinion, is a social contract expressed in one word — a philosophy worthy not only of the clinic, but also of the country … We want to build not only a super clinic, but a super country for Ukrainians. Because they are all superhumans.”

Working with British technology manufacturer Open Bionics, Ivashchuk has already been fitted with a Hero Arm. The custom-made bionic upper limb prosthesis features a suite of light, sound and vibration signals to give users feedback for better functionality. Mastercard funded two of the first prosthetic fittings as the first step in its strategic partnership with Superhumans.

“Innovative and high-quality services are important in all areas of life, and we are convinced that Ukrainians deserve the best of modern technologies,” Inga Andreieva, general manager for Mastercard Ukraine and Moldova, says.

“So many people have lost so much in this war, and our mission is to restore their physical abilities and their sense of self-worth,” says Superhumans CEO Rudneva. “We want them to see themselves as superhumans, proud of their experience, not embarrassed by their injuries. That is part of returning freedom to Ukraine.”

Earlier this year, Ivashchuk and Andrii Hidzun, a soldier who was wounded in an April 2022 mine explosion, traveled to Munich to test their prostheses. Holding a glass of water, gripping a pencil and holding a small ball, both men using their muscle memory to take control of the hand in a matter of minutes.

“When they put on the prosthesis, I didn’t want to take it off,” Ivashchuk says. “Like a toy in childhood, when you really wanted a toy and they finally bought it for you. You walk with it, eat with it, sleep with it.”

Hidzun, 29, was a miner in Novovolynsk, a coal-mining city in the far west of the country, when he was drafted into the army March 9. He served combat duty in Kyiv, Donetsk, Kirovohrad and Mykolaiv, a city near the Black Sea.

Less than a month later, he and his commander near Mykolaiv, listening to the military radio in their vehicle. A shell exploded nearby. They ran out of the car and hid in the trenches, but as the heavy attack continued, they ran to a nearby forest, where a mine exploded. Hidzun lost his arm.

The hardest part, he says, was telling his parents — he is an only child — about his injury. “For a long time, I could not find words to tell my mother what had happened to me,” he says. “Three months. I just didn’t know how to start so that she wouldn’t take it so painfully. Only Dad knew. But I understood that I would not be able to hide … It was extremely hard, but I had to go home and tell the truth.”

Hidzun is not sure what the future holds, but one thing is certain: After he receives his prosthesis at the Lviv clinic, he will go home for a fishing expedition with his father, learning how to hold a spinning rod with his new hand.

Banner photo: Andrii Hidzun shows off a Ukrainian flag he drew with his bionic arm at the opening of the Superhumans Clinic in Lviv.

Inclusion

Helping Superhumans deliver on its promise

Thousands of Ukrainian soldiers and civilians have suffered life-changing injuries. The nonprofit Superhumans has opened a modern rehabilitation center in Lviv to restore their physical abilities and sense of self-worth, and plans to expand its services across the country.

Make a donation