The many faces of Mastercard’s 'Biometric Man'

November 16, 2021 | By Beth Szymkowski

Just about every “Mission: Impossible” movie has a pivotal moment when a character peels off a face mask so realistic it has fooled allies, enemies and facial scanners designed to protect something fabulously valuable or dangerous.

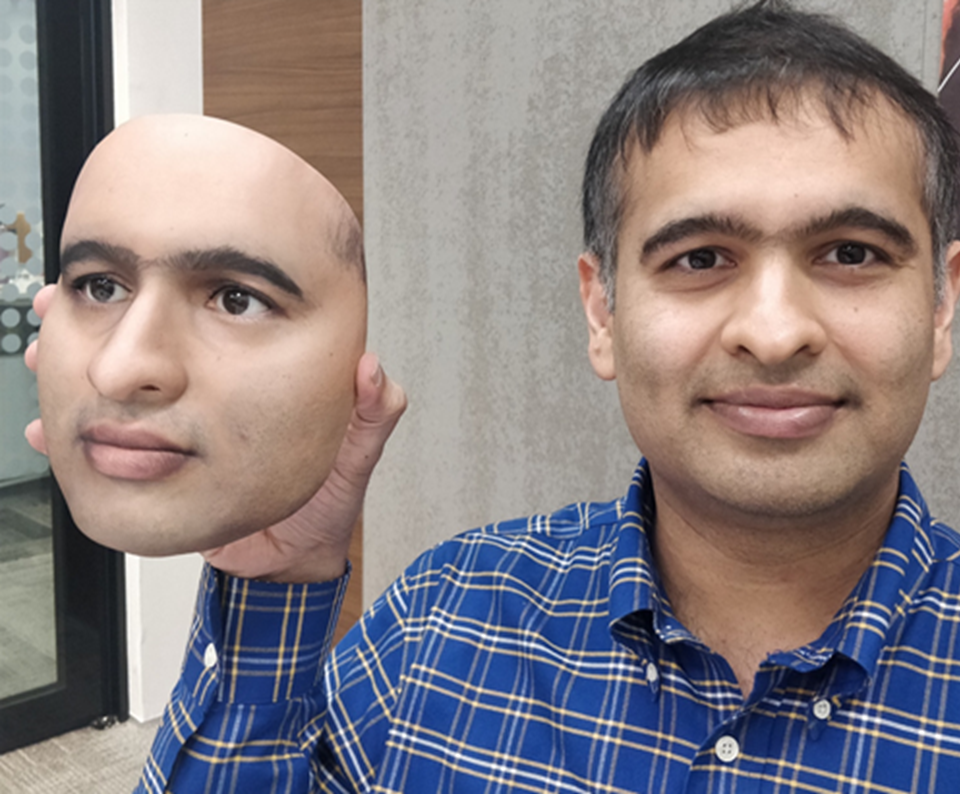

Rajat Maheshwari has such a mask.

But unlike Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt, Maheshwari uses his mask, and a collection of other fake body parts, to put biometric technology through its paces and look for weak spots. If he and his team in Mastercard’s Cyber & Intelligence business can fool — or spoof, in the lingo of the industry — a device with one of their models, it’s back to the drawing board. “The intent is not really to show the world we can spoof the system,” he says. “The intent is to show we can improve the system.”

Biometrics are a more secure way to recognize individuals than passwords, which can be forgotten or hacked. Passwords account for 80% of data breaches, according to the FIDO Alliance, an industry association working on stronger, simpler authentication. Biometrics are also more convenient: Everywhere you go, you take your face and hands with you.

What was once a futuristic scenario — scanners used to identify people by their physical characteristics, like their eyeballs or fingerprints — is now commonplace. One study estimates that biometrics will be used in as many as 18 billion transactions in 2021. They’re not the only tool that fraud prevention experts rely on, says Chris Reid, executive vice president for Identity Solution at Mastercard. Combined with behavioral biometrics, such as the angle at which you hold your phone or the pace at which you type, and other encryption tools and layers of insight, they form a connected intelligence that makes each digital interaction — from payments to identity authentication — more secure without sacrificing a seamless experience for the consumer.

India-born Maheshwari has a computer science background and spent the early part of his career working in semiconductors in China, South Korea and France before landing in Singapore. He joined Mastercard there in 2014 to work in the nascent field of digital wallets. When a client wanted to authenticate payments for a digital wallet using fingerprints, Maheshwari realized he knew nothing about biometrics but wanted to learn. “I was following my passion. I had no clue where exactly I would end up.”

Today he holds several patents in the field of biometrics and authentication, and part of his work involves constantly anticipating how hackers might try to spoof a product. In one case, he was able to fool a client’s facial recognition software by using a black-and-white photo of a face with specialized contact lenses placed on the eyes in the photo. He reported back to the client, who used the information to improve the product. That exchange is at the heart of what he does. “We are making sure our consumers feel safe.”

Rajat Maheshwari tests biometric products that rely on facial identification using a (clearly) custom-made mask crafted by an artist who was part of the crew that created masks for the film "Avatar."

Alvin Tan, the minister of state for Singapore's Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth and the Ministry of Trade & Industry, visited Mastercard's Singapore offices in August and tested out Maheshwari's mask as part of ongoing work to secure the national digital infrastructure.

Maheshwari pressure-tests all kinds of biometrics, from facial identification with his masks to iris recognition through special contact lenses to palm print and vein patterns using prosthetic hands.

He also "spoofs" his own fingerprints to test biometric payment products and other biometric devices.

Not all of the models used in Maheshwari’s lab are as sophisticated as his lifelike mask, which was created by an artist on the crew who had worked on masks for the movie “Avatar.” It can trick most facial recognition software but is too costly and specialized to be a good candidate for widespread spoofing. Maheshwari and his team use models of different qualities and price points to test products, searching for a balance between what is possible and what is feasible for widespread misuse: “Can it be done with one dollar, or do you need thousands, and is it scalable or not?”

His team brings large numbers of subjects into their lab. They’ll ask each person to, say, try to unlock a phone with their fingerprint. In rare cases, even when it shouldn’t, a fingerprint works. That’s what he calls a false match, and to meet Mastercard standards, that can happen only 0.01% of the time. “If I try to access your phone ten thousand times, there is a random possibility I might be able to enter once,” he explains. “That’s the standard we try to meet.”

On the other hand, sometimes biometric readers fail to recognize a legitimate match. This is called a false non-match and is acceptable only if it happens less than 3% of the time. He also tests for verification time, or how fast a device takes to register information.

The work can also reveal unanticipated issues. In one case, a person had a physical limitation that made flattening his hand to capture his thumbprint impossible. It gave the team a new challenge to solve around. “The aim of these tests is not to break the system,” he says. “We are trying to improve the user experience.” In another case, the biometric scanner was not reading a person’s palm print. After several tries, they realized the person had been to a club the night before and had the number 3 written on his hand in invisible ink, which prevented the scan from registering.

The field is constantly expanding. Researchers are perfecting ways to authenticate identity using people’s heartbeats or their movement patterns as they walk, among other things. Tech even exists that can authenticate a person based on the way sound travels in their ear canal, Maheshwari says.

It’s all moving toward a more invisible user experience, and one that may combine more than one biometric modality, like face and iris recognition. Eventually, you won’t need to show anything or keep any device with you. People could be authenticated as they walked through a store or airport, with no need to produce identification or proof of payment. It would all be linked to biometrics.

And speaking of airports, the only downside to his job is when he goes through airport security on a business trip and needs to pack his mask. He gets pulled aside every time he travels with one. Do agents interrogate him and accuse him of being a spy?

Hardly, he laughs. “They take pictures.”

explainer

The future of identification

Physical biometrics, like our fingerprints and our face, have become everyday ways to authenticate ourselves in the digital world. But behavioral biometrics — the unique way we hold our phone, how fast we type, the pressure we apply to the touchscreen, for example — can also help establish our identity online and reduce fraud.

Learn more